The University of Tehran is the oldest university in Iran.It was founded in 1934 and is considered one of the most prestigious universities in the Middle East. (1) (2)

Did I know that back then? Not really. The only attraction for me was the opportunity to spend time away from home and attend the same university as many of my ancestors. Was there any hope for me? Absolutely not.

Before the Iranian Revolution, medical education and healthcare were separate entities, overseen by two distinct ministries. Those working for the science ministry were required to work at a university-affiliated hospital as well as the college. For instance, my father, a hospital staff member, had to treat 40 children, ranging from newborns to 12-year-olds, at the children's hospital each morning, before driving to the university of Tabriz.

After the revolution, the medical science division of the science ministry merged with the ministry of health, forming a new entity. Prior to this change, many of his colleagues emigrated to countries like Germany, France, Britain, and the U.S. I resented him for not doing the same. His argument at the time was that people from around the world were coming to Iran to live and work. While this was true pre-revolution, post-revolution, life became so difficult that almost everyone emigrated, except those imprisoned.

I also never understood why he returned to Tabriz two years after graduating from college, especially considering he was forced to leave the city at the age of six when it was occupied by the Russians.

Most of my relatives lived in Tehran, and we had no close family in Tabriz for a long time until an aunt moved there. Her husband was transferred by the Ministry of Agriculture; it wasn't a choice."

Despite the opinions of many educated politicians who had not been executed or fled the country before the revolution, the new government consolidated its power. They were there to stay. The future looked bleak. Religious extremism grew, personal freedoms were curtailed, the value of the currency plummeted, and, most significantly, an unnecessary war between Iran and Iraq erupted as Iran sought to "export the Islamic Revolution". There was no hope for me.

If I hadn't experienced the free world beforehand and hadn't built my dreams around that experience, perhaps it would have been more bearable. For a while, international travel was banned. As soon as the restrictions were lifted about a year and a half later, another wave of people emigrated.

We stayed put!

The war demanded manpower. As casualties mounted, there was no way to avoid military conscription. At 18, young men were automatically drafted, unless they were enrolled in college. Many hardline revolutionaries believed that attending college was not a valid excuse for shirking the national and Islamic duty of fighting the Iraqis.

I turned 17 in February 1983, and my passport automatically expired on March 20th of that year. The government was revoking foreign travel privileges at the end of calander year they were turning 17 , hoping to prevent many young men from leaving the country and living independently. Spot on. That's what my parents chose for me. My father, a staunch advocate for Iranian higher education, saw no academic reason for anyone to pursue a bachelor's or master's degree abroad.

Instead of logical reasoning, my parents manipulated my emotions. They warned me that my father would be heartbroken and my siblings would lose their father. They claimed that only underperforming students were sent abroad. They insisted that my problem wasn't with Iran but with my family, and that moving to a different city would solve everything.

The final blow came when my mother insisted that it would be embarrassing for the family if I didn't get accepted into any college. This had never happened on either side of the family, though that wasn't entirely accurate.

Being fearful of war and death, and lacking any support, I had no choice. She offered to send me to England, where my aunt lived, or to Australia, where another aunt resided, upon my college acceptance.

Reluctantly, I agreed. In reality, I didn't have a choice. I was still waiting for my allowance to buy the books I wanted. I could not afford leaving on my own!

As my high school graduation approached, my dad informed me about a program between the Iranian Ministry of Science and the Turkish Ministry of Science. They were going to hold an exam in Tehran, and if I qualified, the government would reinstate my travel privileges.

The exam was scheduled between my high school finals, forcing me to travel back and forth to be able to attend my high school exams. I also had to learn to read and write Turkish in less than two months while simultaneously preparing for my own exams.

I flew to Tehran on June 22nd, 1984, took the exam on the 23rd, and then flew back to Tabriz to sit for my final high school exam on 24th.

I aced the exam, missing only one question across various subjects including math, physics, social studies, and Turkish language. I was accepted into my first choice, Civil Engineering at Bogazici University, the top university in Turkey. Within two years, I could transfer to Boston College. My dream was coming true.

Now, it was time to show off. Since I was leaving regardless, there was no point in not answering every question on the university entrance exams. The higher the ranking, the better!

The full-day exam was grueling, but I unexpectedly achieved the highest score in the entire province.

Before the second part of the national exam, the news about my acceptance into the Turkish program was uncertain. Not everyone was approved to leave the country. Despite the uncertainty, I was confident that I would be accepted somewhere, regardless of the outcome of the second exam, which focused specifically on engineering subjects.

I felt disheartened and betrayed. My high scores on the first part of the exam had become a double-edged sword. Confused and overwhelmed by the war, family pressures, and my uncertain future, I struggled to think clearly.

Unfortunately, I was accepted into the Civil Engineering program at the University of Tehran.

On the one hand, the University of Tehran was far from home, offering a degree of independence. On the other hand, it wasn't significantly different from Tabriz. Ultimately, the government denied my request to leave, believing I had no intention of returning. Perhaps, for once, they were right.

Long story short, I went to Tehran, attended classes half-heartedly, and failed over half my courses in the first semester. I failed again the following semester. Disillusioned, I returned to Tabriz, ready to pursue my own path. However, my family, particularly my father, ignored my pleas. Eventually, a new rule was implemented allowing college students to leave the country if a dying relative requested it. My genuinely ill aunt wrote a notarized letter from the hospital, which I presented to the Ministry of Science in Tehran. I applied for summer school to demonstrate my academic capabilities and successfully passed all courses with A+ grades.

The university's admissions office had to weigh in, and unfortunately, my Thermodynamics professor, who was also one of the VPs, denied my request. I was back to square one. I continued to fail exams, putting myself at risk of expulsion and potential military conscription. As the Iranian military and Revolutionary Guard struggled in the war, and Iraqi forces made significant territorial gains, the government responded by closing universities and sending male students to the front lines.

When I returned, I didn't re-enroll for the semester, leading to my dismissal from the university. I planned to complete my military service, work odd jobs to save money, and eventually leave the country permanently.

Many factors contributed to my change of heart and new direction in life. However, it was my dear and close friend, Alireza Aliasgharlou, who, knowing my history and having repeatedly tried to help me, encouraged and supported me to re-enroll in college. Despite having few credits and over 40 failures, I managed to complete my degree in just 2.5 years.

I met a girl and we became serious. To encourage her to apply for a master's degree, I also started to pretend I am interested and took the exam. I was conditionally accepted into the Traffic Engineering program at Sharif University of Technology. I had no intention of pursuing the degree. Ironically, she was graduated from Sharif and later enrolled in the Electrical Engineering program at the University of Tehran for her master's degree. (I often joke that my wife is the real engineer, given her education at the University of Tehran.)

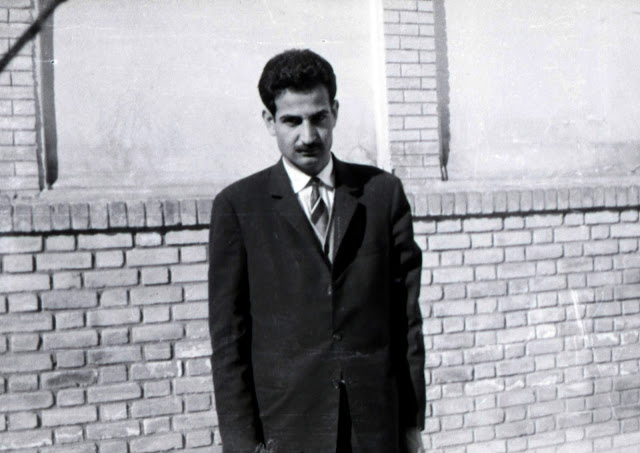

This year marks our 40th anniversary of admission to the University of Tehran. In preparation for the ceremony, I was invited to give a short speech. This brought back a flood of memories, mostly of failures, but also of the lifelong friendships I forged along the way. Much to my surprise, I ended up speaking for over seven minutes!

The Iranian Revolution not only shattered hopes and dreams but also robbed us of beautiful moments over the past 45 years. We lost cherished friendships and simple joys like celebrating birthdays, weddings, and graduations together. Many of us now live scattered across the globe, rarely having the chance to connect.

The Iranian government has stripped us of our livelihoods and offered nothing in return, only empty promises and lies.

Comments

Post a Comment